Launched in 2022, the Indigenous Leaders stamp series highlights the contributions of modern-day leaders who have dedicated their lives to preserving their culture and improving the quality of life of Indigenous Peoples in Canada.

We spoke with this year’s honourees and their loved ones about the importance of language preservation and protection.

Julia Haogak Ogina: Linguist, author, drum dancer

Witnessing the erosion of her Inuit heritage spurred Ogina to devote her life to revitalizing the culture and languages of her ancestors. An accomplished author and drum dance teacher, she has helped to retrieve and preserve drum dance songs – which she sees as a critical conduit for traditional knowledge. In nearly two decades with the Kitikmeot Inuit Association, she has contributed to the creation of a regional language framework and programs promoting oral learning and knowledge transfer.

What is drum dance?

It’s a lot of things. First, it’s a celebration, a way of expressing the experiences that Inuit have. It tells the stories of the land, the animals, the travels, and the emotional state of humans. Drum dancing strengthens identity, empowers people, it grounds people. It’s a time to visit with one another.

Historically, people gathered for drum dancing when there was an abundance. When hunters get together after being on the land, the hunters would visit with each other, and they shared experiences. That becomes their story, their song.

Some of the stories that are told are so old, we don’t know who the song creators are. And the stories that are in the songs, they’re a window to a time that doesn’t exist today.

Drum dancing describes a lot of feelings, it describes hardships and getting through the hardships. It tells a lot of stories of who we are, how we are. And it uses language to describe emotion, to describe the season, to describe where they’re at, be it on the ocean ice in the winter, be it on the land in the spring and summer, inland or on the coast. It’s really descriptive, the language.

Historically, while they’re waiting for other hunters to arrive, they’re singing old songs, songs that have been shared before. When all the hunting groups have arrived, that’s when they share new songs, new stories, to express feelings, connect values and beliefs with the animals and with the environment around them.

The terminology used in those drum dances is not used in everyday language, just in the songs, and that’s how language was kept alive. That was their platform for sharing, when they had drum dance gatherings.

Who taught you drum dance?

I grew up in drum dance. My great grandmother, my grandparents, my mother, my dad, they were all story tellers. They all sang songs; they all visited each other, then songs would start, and drumming would start. That was my childhood, my teenage hood.

I have a drum at home. I still sing. My granddaughters sing with me, and I have friends that come over and sing with me.

What is the connection between drum dance and language preservation?

Without the stories, there’s no dance. Without song leaders, there’s no stories.

Knowing the language lets you continue to tell the stories as accurately as the original storyteller told them.

Why did you want to re-introduce drum dance to your community?

The most important thing to me was how rich these stories were and that there was a gap from the elders to the middle generation to the youth and the children. There was a gap of people who didn’t understand that [the richness of the stories].

Elders, when they sing their songs, they tend to close their eyes and go right into the song and the rhythm. I used to wonder why they did that. And it’s them watching their story unfold, their experiences unfold as they sing the song.

I can connect to that because I can understand the majority of the song. But there were some terms that I didn’t understand, so if I didn’t understand them as an adult, then chances are the young people didn’t understand a whole lot more of the story and it just becomes a dance. It just becomes an old story they don’t understand.

What caused that knowledge gap between generations?

When we had the first contact with Inuit in our area, those expeditions in the late 1800s, early 1900s, missionaries were on board, and they brought the bible and that has its own values and belief system that’s not the same as what Inuit had as their values and belief system.

Without fully understanding why Inuit people drum dance and what drum dance is about, the missionaries were telling our people they had to stop doing certain things because it’s not in the bible. So some of the songs from that time are not practiced or told anymore.

The past two years, I’ve been doing leadership with my husband and at a community space where we do drum dancing once a week. We have the drums, we maintain the drums, and we sing and dance with the community. I have been teaching my daughter, along with my granddaughters, to lead. I’ve been stepping back to see who from the younger generation is going to step up.

We’re at a point now where people are feeling stronger and wanting to share. And they’re learning more about reconnecting with the language maintainers or the maintainers of the songs. They’re still around. They are few, but they’re still around! And there’s a bigger generation that wants to connect to that. This generation that’s learning to lead is now desiring to create their own songs and stories.

Preparing the next generation, that’s how our language is kept alive.

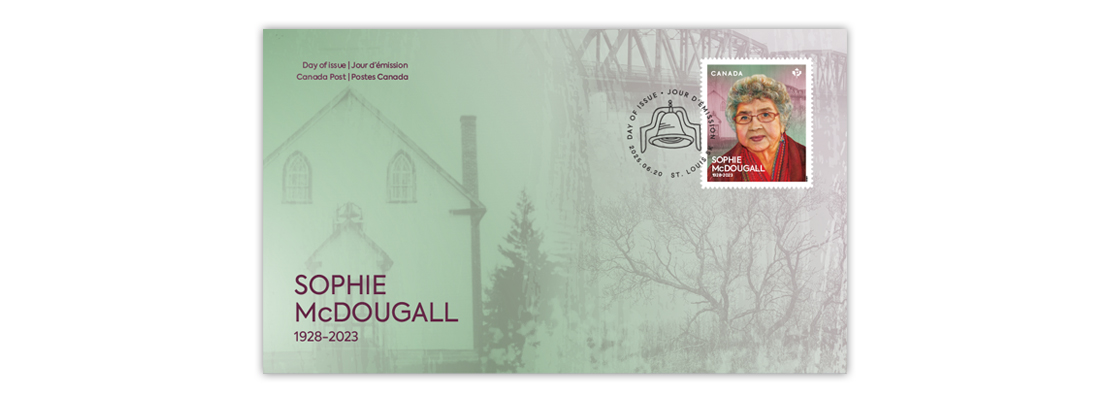

Sophie McDougall: Teacher, Elder, Language Keeper

McDougall (1928-2023) shared extensive knowledge of her culture and language with generations of students and community members. Born in St. Louis, Saskatchewan, she worked as a schoolteacher before dedicating her life to documenting and teaching Michif and the regional dialect Michif French. The traditional language of many Métis, Michif is categorized as critically endangered by UNESCO. McDougall received the Order of Gabriel Dumont Gold medal in recognition of her lifetime of service to the Métis of Canada.

Angela Rancourt is a Métis educator and friend of Sophie McDougall.

Cindy Gaudet is a Métis researcher and educator, and friend of Sophie McDougall.

Tell us about Sophie…

Cindy: She was tenacious, super intelligent, a bright presence, and generous with her time, with her love, and with sharing what she knew.

Angela: She was our storybook. She was a database of all our stories.

Cindy: Everyone would go to Sophie if they needed to know something. Are these people related, how are we related, when did the church get moved, what was going on at that time, when was that event…? She was our kinship archives.

Angela: She played such a vital role in sharing pride in being Michif and identifying as a Metis person.

She was passionate about sharing her language. Why is it so important to preserve and protect Michif French?

Cindy: Language can’t be thought about in isolation of social, cultural, political and relational contexts, so when we lift up the language, it lifts all those different elements. What I’ve learned from working with Sophie is that language is about how we live, who we are.

Angela: You think about it differently than learning a language in the traditional sense, where you’re learning to conjugate verbs, and you’re learning to count to 10, and you’re learning your colours… When we learn Michif, we could learn it that way, but are we learning anything about us? We are not. So we need to rely on the traditional ways that our families passed down language, and that was the conversation at the kitchen table. Because the stories that are tied to the language are where you learn about yourself, and your families, and your lands, and your histories.

In what other ways did Sophie work to preserve and protect her language?

Angela: We started a Michif early-learning program in the school shortly after we worked on the card project. We realized we had to support families and communities better in learning the language because going to classrooms and teaching three and four and five-year-olds would not work in order for the language to survive. We needed to make space for families to be connected to the language and it was Sophie who said, “Get it on the phone, get it on their phones!” So we needed an app.

Learn Michif French is available for Apple and Android and provides over 3,000 translations and audio pronunciations as well as almost 800 phrases provided by Sophie and other Language Keepers.

Angela: Now our community has moved forward with the development of a Michif French high school curriculum. That was something Sophie always talked about wanting to do. We didn’t quite make it; it started about a year after she left us.

The entire curriculum is based on her stories. It’s framed around who are we, who am I, where are we? and focusses on identity, and land, and relationships, and Michif culture and pride.

The entire concept of the curriculum is based on the visiting way at the kitchen table. It’s all learned by doing – cooking together and speaking in the language, and gardening together, and going fishing together and just sitting down and having tea and visiting.

Cindy: She recreated learning from the kitchen table in the classroom, where Sophie was a guest, visiting auntie, visiting Elder. Making those connections in the school is really kind of radical in some sense.

Angela: Now a Michif French curriculum exists in our high school. I started teaching that just this year. It’s being offered on a provincial level now, instead of a localized level, and I think that’s Sophie’s dream. She said she never imagined a day in her life where Michif would be spoken in the schools.

Cindy: It’s her carrying on through us and with us.

Sophie loved Mother’s Day. Her funeral was held on Mother’s Day, 2023, and you are speaking about her the day after Mother’s Day 2025. What did Sophie mean to you personally?

Angela: Sophie continues to be the foundational inspiration of the work that we’re doing in the community, which is the foundation of my dissertation and practice. So Sophie was my 94-year-old best friend and my guiding light.

Cindy: She carried the land, she carried the people, she carried the spirit of the world all around her. It doesn’t matter where I am, she’s there because that’s how big her spirit is.

Bruce Starlight: Linguist. Elder, Knowledge Keeper

Known as Dit’óní Didlishí (Spotted Eagle), Starlight is one of the last fluent speakers of the Tsúut’ínà language. For more than five decades, he has worked hard to save his language and culture from extinction. Starlight founded the Tsúut’ínà Gunáhà Násʔághà – an institute dedicated to the revitalization of his mother tongue – and was language commissioner for the Tsuut’ina Nation. An accomplished teacher and speaker, he has developed extensive materials for Tsúut’ínà instruction, including dictionaries and recordings. Starlight received an honorary doctorate from Mount Royal University in 2023.

Why is preserving Tsúut’ínà important?

If you don’t preserve your language, you will never preserve your identity.

We’ve lost our language because of the residential schools, colonialism, bureaucracy… You name it, we’ve had those impacts on our language that’s made some of the language unrecoverable. But what we do have left, and what we are speaking, it’s got life. It has a life of its own. What did Shakespeare call it? Metaphysical. That’s our language. It’s metaphysical and it’s our being, it’s our DNA.

Preservation is very important because it’s our knowledge, what we grew up in. And there’s things you can never translate, especially those words of empathy and sympathy. You can never translate them into English. It’s impossible.

Reversing that loss of language, and that loss of feeling, is what language preservation is all about. Regaining it is difficult. Lip service and throwing money at the problem will not solve it. There has to be a buy-in so that languages will survive. Like archiving, like recording, like podcasting…any way we can, we must keep our languages alive.

What is being done to reinvigorate Tsúut’ínà?

One of the things we say about our children is that pride and identity is with them until they get on the bus and enter the doors of the non-Indigenous schools. We had my grandson at a gathering trying to get real Indigenous content in the Alberta curriculum. And he said, “All we learn about our culture is Orange Shirt Day.”

So we’re asking the provincial government to revisit the Aboriginal content in our school curriculum. And by Aboriginal content we mean that it cannot be just one day for the 10 months of our children’s school life. It’s got to be every day.

Language preservation is a lifelong journey that has given me hope. I take my hat off to the young people that are involved in it. It may not be my Tsúut’ínà, but it is Tsúut’ínà, and it’ll grow.

What can individuals do to help?

Well, just take an interest. I don’t know what Indigenous people are near you, but ask them, “How do you say, ‘how are you?’ and how do you respond?” That is the initial buy-in.

But to sit back and say, “Oh, that’s very interesting. That’s a very cute language…” Well, that’s not cute. It’s a language of survival because we’re still here and, for all intents and purposes, we should have died out long ago.

So how do we deal with the white elephant in the room: racism, marginalization, the lack of inclusion? And the lack of putting your hand out and saying, “Come, I’ll help you”? That’s what is needed.

How did language preservation come to be so important to you?

I’ve been many things. I’ve been a logger, I’ve been a farmer, I’ve been a rancher…

When my dad passed away, and there was no one to look after my siblings and my mom, I had to quit high school. I had to work and struggle and feed my family. I went to university in my late 40s [Starlight studied linguistics].

My advantage was my immersion in the Tsúut’ínà language, but I needed to take linguistics in order to fine-tune my knowledge. I thought I was a fluent speaker. I thought I knew everything, but I didn’t.

I was successful in getting us a small grant [for the Tsúut’ínà Gunáhà Násʔághà institute, in the early 2000s] and we started to record the people that were still around at that time and who were involved in it [preserving Tsúut’ínà].

There were three fluent speakers that started it [the Tsúut’ínà Gunáhà Násʔághà institute], and of those three, there’s only one of them left. That’s myself. So I always tell people, “Hurry, I’m getting old.” You know, “Record me as much as you can, so that you’ll have what I have, or remnants of it.”

Fourth Indigenous Leaders stamp issue honours Inuit, First Nations and Métis leaders

Available now