During the First and Second World Wars, thousands of immigrants and their Canadian-born children were torn from their homes, stripped of their freedoms and forcibly confined to internment camps across the country. This affected German, Italian, Japanese and Ukrainian communities, among many others, as well as Jewish refugees, socialists and even conscientious objectors.

Canada Post’s latest stamp issue seeks to shed light on this dark chapter, when the Canadian government not only confined thousands in internment camps, but also compelled tens of thousands to register and regularly report to authorities in the name of national security. The stamp aims to raise awareness about these events and honour the resilience of those who endured forced displacement, confinement and hardship.

“This is a complicated and, at times, messy and confusing story encompassing arrest, displacement, and confinement,” write Rhonda L. Hinther and Jim Mochoruk in Civilian Internment in Canada: Histories and Legacies. “And this story spanned — and still spans — war and peacetimes, having affected persons from a wide variety of political backgrounds and ethno-cultural communities.”

First World War

On August 15, 1914, in the opening month of the First World War, the federal government issued a proclamation allowing for the arrest and detention of immigrants from Germany and the Austro-Hungarian Empire if there were “reasonable ground” to suspect them of hostile acts against Canada or aiding and assisting “the enemy.”

One week later, Parliament passed the War Measures Act. This law gave Cabinet sweeping powers, including the power to suspend civil liberties such as the right to a fair trial before detention.

Official records state that more than 8,500 men were held at internment camps and receiving stations across Canada. This included people from:

- the Austro-Hungarian Empire, including more than 5,000 Ukrainians, as well as Croats, Czechs, Hungarians, Jews, Poles, Romanians, Serbs, Slovaks and Slovenes;

- the Ottoman Empire, including Armenians and Turks;

- the German Empire; and

- Kingdom of Bulgaria.

To keep their families together, 81 women and 156 children voluntarily joined their male relatives in internment. Homeless and unemployed people, conscientious objectors and members of outlawed political groups, mainly socialists, were also interned.

Detainees lived in austere and at times harsh conditions. Some were forced to work on labour-intensive projects. More than 100 died. Some died from disease, injury and suicide. Others were shot trying to escape. Many were buried in unmarked graves, far from home and loved ones.

Another 80,000 people, mostly Ukrainian, were forced to register as “enemy aliens,” including Canadians with parents who had immigrated from a country at war with Canada. “Enemy aliens” were forced to regularly report to authorities and had their rights to speech and association severely restricted.

Fighting during the First World War officially ended with the signing of the Armistice on November 11, 1918. However, some people remained held in internment camps until after the conflict formally ended on January 10, 1920.

Second World War

The War Measures Act was once again invoked on August 25, 1939, one week before the outbreak of the Second World War. This gave the government the power to detain anyone believed to be a threat to the public or the state.

Over the next six-plus years, as many as24,000 people were interned across the country – sometimes alongside enemy prisoners of war. They included German Canadians, Italian Canadians and Japanese Canadians. Jewish refugees from Germany and Austria were also detained alongside socialists, conscientious objectors and other “subversives.”

As in the First World War, many people were also required to register with the government. More than 20,000 Japanese – the majority Canadian citizens – were forced from their homes on the West Coast. Their property was confiscated and later sold by the government.

The War Measures Act remained in effect until December 31, 1945, but the legal restrictions against Japanese Canadians weren’t lifted until April 1949.

Redress

Some of the communities affected by internment during the two world wars have lobbied for redress, including but not limited to official apologies and financial reparations. Central to each community’s motivation for redress has been a desire for Canadians to learn from the past.

Stamp issue and design

Emphasizing themes of separation and displacement, Canada Post’s latest stamp issue reminds us of the many lives and communities affected by internment in Canada during the two world wars.

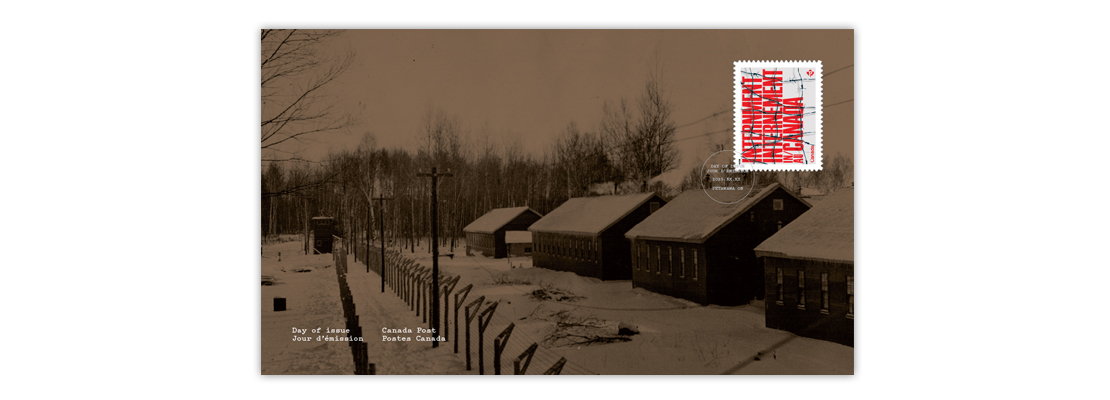

The stamp features bilingual vertical text in red against a grey background, with barbed wire over the words, and is designed to capture the gloom and fear of Canada’s internment camps. The stamp booklet and Official First Day Cover both feature links to Petawawa, Ont., where internment operations were carried out during both world wars.

The cover and back of the stamp booklet include details from a certificate of release from the Petawawa camp during the First World War. The Official First Day Cover features a photograph of the Camp 33 internment camp in 1940, during the Second World War.

The stamp is also cancelled in Petawawa. The simple cancel is reminiscent of the date stamp used by Canadian internment operations.

New stamp draws attention to the legacy of civilian internment in Canada

Available now