With roots dating as far back as the Victorian Era, Hanlan’s Point — a public beachfront on the western shores of the Toronto Islands — is recognized by the City of Toronto as the oldest continuously queer space in Toronto and Canada, and one of the ten oldest surviving queer spaces around the globe.

“When it comes to Hanlan’s, there’s queer history built into every grain of sand on the beach,” Travis Myers tells Canada Post. Myers is co-founder of Friends of Hanlan’s, a non-profit organization that studies Hanlan’s unique past and works with local community leaders to limit commercial development on the historic site.

“To be gay, lesbian, bisexual, trans, you couldn’t be yourself on the mainland,” Myers explains. “So [Hanlan’s Point] was a respite… an escape for people to get away from prying eyes. And what they found when they got there was other people like themselves.”

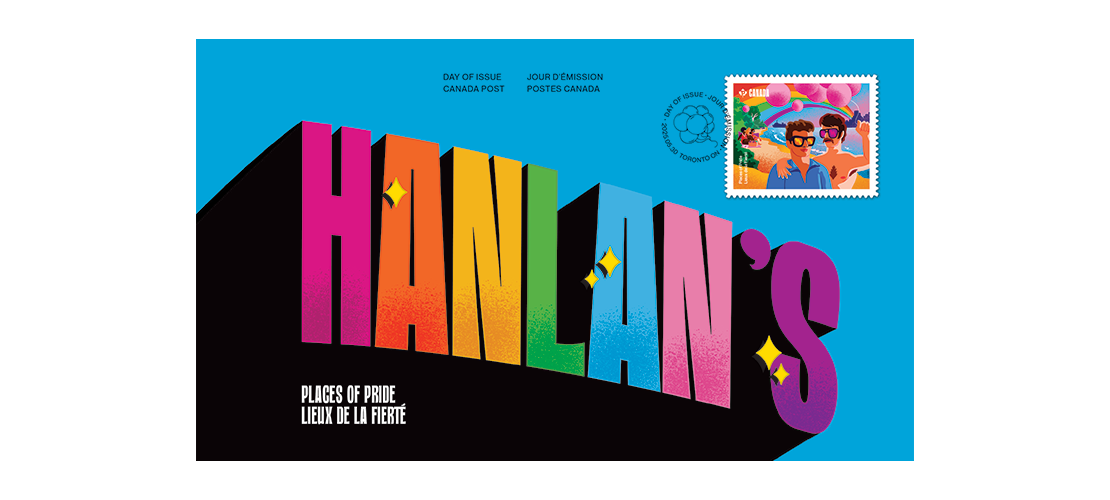

Hanlan’s status as a safe space for communities was entrenched on August 1st, 1971, when it became the site of Toronto’s Gay Day Picnic, heralded by the City of Toronto as the first organized “Pride” event and a precursor to the annual Pride events that take place across Canada each summer. The Gay Day Picnic came at a pivotal moment – and is the inspiration behind one of Canada Post’s new “Places of Pride” stamps, which commemorate spaces across the country that Canada’s queer community fought hard to make their own.

“By 1971, homosexually had been decriminalized for two years in Canada. People think of it as a watershed moment,” says Myers. “But that’s not how it was in reality.” With Canada’s queer populations still facing prejudice and discrimination in their everyday lives, a group of activists began to draft what was called the “We Demand” letter intended to be delivered to Parliament in Ottawa. The letter outlined various rights that were still being withheld, and the Gay Day Picnic in Toronto was an opportunity to put the finishing touches on the We Demand letter before taking it to the nation’s capital.

“When you hear ‘Gay Day Picnic,’ it sounds like a little fun party,” says Myers. “But it’s always been political. It’s always been about securing rights and making sure that queer people can live openly and freely.”

Following the event, Gay Day Picnic organizers, along with other community leaders from across Canada, travelled to Ottawa to present the We Demand letter to the government. And over the course of the following decades, fueled in part by the success of that summer day at Hanlan’s Point Beach, each went back to their respective cities and continued to work toward achieving equality for Canada’s 2SLGBTQIA+ populations.

“Every time I say that I’m queer at work,” says Myers, “or every time I walk down the street and I see a rainbow flag, [I think] ‘It’s those people on that beach who did that for me.’”

“The difference between that day on the beach and the Pride [celebrations] that we have now feels like it couldn’t be any bigger,” Myers notes. “But when it comes down to [it], that same spirit is still there: It’s people who want a better world for queer people. It doesn’t take glitz and glamour to make change happen,” he adds. “All it takes is the willpower.”

New Places of Pride stamp remembers the pivotal Gay Day Picnic at Hanlan’s Point in Toronto

Available now